Important Black Lung Decision: Fourth Circuit Affirms Miner’s Award in Hobet Mining, LLC v. Epling, Discredits Physician’s “Argue in the Alternative” Opinion

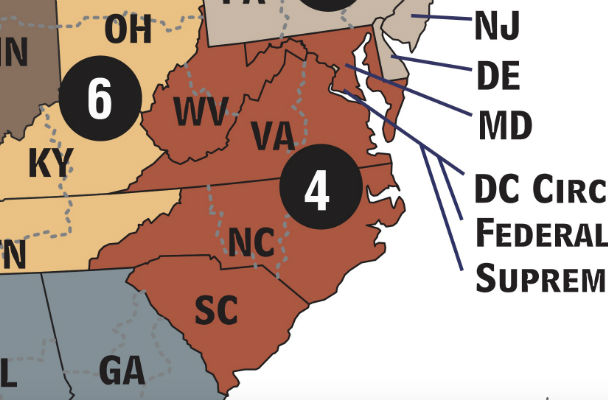

On Friday April 17, 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit issued a published decision in an important case: Hobet Mining, LLC v. Epling, 783 F.3d 498 (4th Cir. 2015) (slip opinion here). The court (via an opinion written by Judge Harris and joined by Judges Floyd and Keenan) affirmed Mr. Epling’s award of benefits, concluding that the ALJ properly applied the rebuttal standard and discounted the opinion of the company’s expert, Dr. Hippensteel, who initially denied that Mr. Epling had pneumoconiosis but then argued in the alternative that even if he had pneumoconiosis, it would not contribute to his disability.

Epling is significant for three reasons:

First, Epling is the case that the Fourth Circuit referred to in over a dozen abeyance orders, meaning that the court has been waiting to decide Epling before dealing with similar issues in other cases. Because Epling and Bender (in which the Fourth Circuit recently issued a major decision covered here) were argued back-to-back before the same panel and both resulted in decisions that are favorable to miners, this bodes very well for claimants with cases in abeyance and otherwise pending.

Second, as a stand-alone decision, Epling is also significant because it is a published decision that provides strong support for an ALJ’s authority to discredit physicians’ opinions that deny that a miner has pneumoconiosis, but then include a pro forma hypothetical position that says that even if the miner does have pneumoconiosis that it would not contribute to disability or even explicitly acknowledge through a supplemental opinion that the miner does have pneumoconiosis. This holding makes it more difficult for physicians to simultaneously argue that a miner does not have a black lung while also arguing that any black lung would not contribute to disability.

Lastly, being the first black lung decision after the Fourth Circuit’s decision in Bender—which held that the rule-out standard applied to operators seeking to rebut a presumption of disability causation—Epling provides further clarification for how the rule-out standard applies. In Epling, the court held in footnote 4 that the marginal difference between a rule-out and “substantially contributing cause” standard was not dispositive in the case, so the court did not need to reach the issue. The court noted, however, that its recent decision in Bender addressed and rejected the company’s argument. The court’s introductory discussion of the applicable law provides a succinct and forceful statement of the standard for cases involving the “fifteen-year presumption,” which favors disabled miners with at least fifteen year of qualifying coal-mine employment.

Facts

Carl Epling worked for over 21 years in underground coal mines, ending in 1999. Mr. Epling filed his claim in 2007. Because he is disabled from a respiratory perspective and has at least 15 years of qualifying coal-mine employment, the ALJ applied the fifteen-year presumption and shifted the burden to Hobet Mining to rebut the presumption. Hobet Mining conceded that Mr. Epling has pneumoconiosis but argued that it did not cause his disability.

Hobet Mining’s position was based on the expert opinion of Dr. Kirk Hippensteel, who expressed his opinion over the course of multiple documents. At first, Dr. Hippensteel denied that Mr. Epling has pneumoconiosis and said that his disability was caused by other causes (obesity and sleep apnea). At the same time though, Dr. Hippensteel said that even if it were hypothetically true that Mr. Epling had pneumoconiosis, it would not contribute to his disability. Dr. Hippensteel provided little support for this, relying on the opinion of another physician that the ALJ discredited. Later in the case, Dr. Hippensteel changed his opinion about pneumoconiosis. He acknowledged that Mr. Epling does have pneumoconiosis, but declined to revisit the portion of his opinion dealing with disability causation. Dr. Hippensteel repeated his previous conclusion that pneumoconiosis did not contribute to Mr. Epling respiratory disability.

The ALJ determined that Dr. Hippensteel’s disability-causation opinion was entitled to “little weight” because Dr. Hippensteel failed to diagnose pneumoconiosis and failed to recognize the latent and progressive nature of pneumoconiosis. The ALJ thus awarded benefits to Mr. Epling. The Board affirmed, holding that the ALJ’s opinion was rational and that neither Dr. Hippensteel’s hypothetical assumption of pneumoconiosis nor his later acknowledgement of pneumoconiosis salvaged his opinion.

Fourth Circuit Opinion

The court first provided a very well-written introduction applicable in fifteen-year presumption cases. I am going to quote it at length because it is as good of a four-paragraph introduction into current legal issues being litigated in black lung cases as exists.

The Black Lung Benefits Act (“Act”) provides benefits to “coal miners who are totally disabled due to pneumoconiosis,” popularly known as black lung disease. 30 U.S.C. § 901(a). To prove entitlement to black lung benefits in the absence of the fifteen-year presumption, an individual must show that he has pneumoconiosis arising from coal mine employment,1 and that this disease is a substantially contributing cause of his totally disabling respiratory or pulmonary impairment. See Mingo Logan Coal Co. v. Owens, 724 F.3d 550, 555 (4th Cir.2013).

“[T]he existence and causes of pneumoconiosis are difficult to determine,” and Congress accordingly has “established a number of evidentiary presumptions to assist miners in proving their claims.” Broyles v. Dir., Office of Workers’ Comp. Programs, 824 F.2d 327, 328 (4th Cir.1987). Among them is the fifteen-year presumption at issue in this case, 30 U.S.C. § 921(c)(4), which was enacted in 1972, eliminated in 1981, and then restored in 2010.3 The fifteen-year presumption is expressly intended to “[r]elax” the “often insurmountable burden” of proving a black lung claim for the special class of “miners with 15 years experience who are disabled by a respiratory or pulmonary impairment.” S. Rep. 92–743 (1972), reprinted in 1972 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2305, 2306. Through the presumption, Congress has “singled out” this group of miners for “special treatment,” making it easier for them to show their entitlement to benefits. Regulations Implementing the Byrd Amendments to the Black Lung Benefits Act: Determining Coal Miners’ and Survivors’ Entitlement to Benefits, 78 Fed.Reg. 59102, 59105–07 (Sept. 25, 2013); see also West Virginia CWP Fund v. Bender, ––– F.3d ––––, No. 12–2034, slip op. at 23 (4th Cir. Apr. 2, 2015).

To that end, § 921(c)(4) provides that,

if a miner was employed for fifteen years or more in one or more underground coal mines, … and if other evidence demonstrates the existence of a totally disabling respiratory or pulmonary impairment, then there shall be a rebuttable presumption that such miner is totally disabled due to pneumoconiosis.

Under the presumption, if a claimant has at least fifteen years of underground coal mine employment and a qualifying respiratory or pulmonary disability, a rebuttable presumption arises that he is entitled to benefits. In other words, we presume both prongs of the showing required for benefits eligibility: that the claimant has pneumoconiosis arising from coal mine employment, and that this disease is a substantially contributing cause of his disability. See Mingo Logan, 724 F.3d at 555.

A coal mine operator may defeat the miner’s claim by rebutting either of these presumptions. First, an operator may establish that the miner does not have pneumoconiosis arising from coal mine employment. 20 C.F.R. § 718.305(d)(1)(i). Second, the operator may establish that “no part” of the miner’s disability was caused by such a disease, id. § 718.305(d)(1)(ii), a standard under which it must “rule out” the mining-related disease as a cause of the miner’s disability, Bender, slip op. at 8; Rose v. Clinchfield Coal Co., 614 F.2d 936, 939 (4th Cir.1980).

(footnotes omitted).

Before analyzing the ALJ’s opinion on the medical evidence, the court noted in footnote 4 the debate about the proper standard for coal operators seeking to rebut a presumption of disability causation. The court declined to issue a holding about Hobet Mining’s argument against the rule-out standard because the court determined that the rebuttal evidence was insufficient under either a rule-out standard or Hobet Mining’s suggested “substantially contributing cause” standard. However, the court cited its recent decision in Bender which rejected an argument against the rule-out standard. This footnote combined with the court’s previous statement of the standard (“the operator may establish that “no part” of the miner’s disability was caused by such a disease, a standard under which it must “rule out” the mining-related disease as a cause of the miner’s disability” (internal citation omitted)) suggests that arguments against the rule-out standard for disability causation will not fare well in future cases before the Fourth Circuit.

The Fourth Circuit then turned to its analysis of whether the ALJ properly discredited Dr. Hippensteel.

The court first provided background on the weight to be given to physicians’ disability opinions that are based on a premise that pneumoconiosis does not exist when the ALJ determines that, in fact, pneumoconiosis does exist.

The court said, “Long-standing precedent established that a medical opinion premised on an erroneous finding that a claimant does not suffer from pneumoconiosis is ‘not worth of much, if any, weight’ particularly with respect to whether a claimant’s disability was caused by that disease.” (quoting Grigg v. Director, OWCP, 28 F.3d 416, 419 (4th Cir. 1994)). Described as a “common-sense rule,” the court said, “opinions that erroneously fail to diagnose pneumoconiosis may not be credited at all, unless an ALJ is able to ‘identify specific and persuasive reasons for concluding that the doctor’s judgment on the question of disability causation does not rest upon’ the ‘predicate[]’ misdiagnosis.” (quoting Toler v. E. Associated Coal Co., 43 F.3d 109, 116 (4th Cir. 1995)). And even if such reasons exist, such a physician opinion may be give only “little weight.” (quoting Scott v. Mason Coal Co., 289 F.3d 263, 269 (4th Cir. 2002)).

The court then applied this standard, holding that because the ALJ gave “little weight” to Dr. Hippensteel’s opinion—and under cases like Scott this is the most weight that an “argue in the alternative” physician’s opinions can be given—then the ALJ was barred from giving Dr. Hippensteel any more weight.

The court said that moreover, Dr. Hippensteel’s opinion did not provide “specific and persuasive reasons” to show that his disabilty causation opinion was independent from his view about the existence of pneumoconiosis. The court said “it is not enough for the expert simply to recite, without more, that his causation opinion would not change if the claimant had pneumoconiosis. Rather, such an alternative causation analysis, like any causation opinion, must be accompanied by some reasoned explanation—in this context and explanation of why the expert would continue to believe that pneumoconiosis was not the cause of a miner’s disability, even if pneumoconiosis were present.” Rather, the court described Dr. Hippensteel’s first opinion as “just a ‘superficial hypothetical.'” (quoting Soubik v. Director, OWCP, 366 F.3d 226, 234 (3d Cir. 2004)). Dr. Hippensteel’s “late-breaking determination” that Mr. Epling’s pneumoconiosis was not just hypothetical but confirmed by the CT scan evidence did not warrant his opinion being given more weight because “At no point after diagnosing pneumoconiosis did Hippensteel revisit his earlier opinion to take into account the elimination of what had been the factual predicate for his view.“

The court also added that an additional reason for the ALJ to discount Dr. Hippensteel’s opinion was his testimony that “it would be unusual for [Epling] to have pneumoconiosis ten years after he ended his coal mine employment” which conflicts with accepted view and the Department of Labor’s regulations that recognize pneumoconiosis as “latent and progressive.” The court noted that the ALJ was entitled to take this disagreement into account.

Analysis

As stated at the beginning of this post, Epling is an important decision in multiple regards.

On the Court’s holdings in this case, the court’s statements regarding Dr. Hippensteel’s opinion provides strong law against “argue in the alternative” physicians’ opinions. What Epling makes clear is that, at most, such opinions can be given “little weight” and to be given any weight, there have to be “specific and persuasive reasons” for doing so.

Epling encourages coal companies to either have a physician focus on the existence of pneumoconiosis or on what contribution pneumoconiosis would have on a disability. In other words, company physicians who attempt to address both prongs of the rebuttal standard are not likely to be given much—if any—weight on disability causation. Granted, in legal pneumoconiosis cases the two prongs overlap, but Epling show that a failure to diagnose pneumoconiosis essentially dooms the remainder of a physician’s dual opinion.

The court’s decision not address the rule-out standard is an implicit holding that (as the court has done in cases like Mingo Logan Coal Co. v. Owens, 724 F.3d 550, 554–56 (4th Cir. 2013), and West Virginia CWP Fund v. Gump, 566 F. App’x 219, 222–24 (4th Cir. 2014)), an operator must meet a threshold showing that the marginal difference between a rule-out and “substantially contributing cause” standard makes a difference before the court will even consider a challenge to the rule-out standard. And the court’s citation to Bender in footnote 4 and in the above-quoted statement of the standard applicable to the case, suggests that the court sees Bender as the resolution of the debate about the rule-out standard.

Thus, unless a coal company can attract en banc or Supreme Court review, rule-out is established as the law in the Fourth Circuit.

The next areas of interest in black lung law before the courts of appeals are the abeyance cases and the standard for rebutting pneumoconiosis.

Unless coal operators withdraw their appeals and agree to pay benefits, there is likely to be a waive of summary affirmances in cases that have been held in abeyance pending Epling.

However, there could be substantive litigation and an important decision yet to come about the standard for rebutting the existence of pneumoconiosis. This is a complicated issue because pneumoconiosis includes “legal pneumoconiosis,” which has a definition that incorporated a causation standard into its definition. Because both Bender and Epling involved facts in which pneumoconiosis was conceded, the Fourth Circuit did not address this issue. There are strong hints in both decisions that the court is comfortable with the fifteen-year presumption and considers operators arguments against it to be specious. (For some of the language from Bender that could carry over into this issue, see the post about Bender.)

The attorney for Mr. Epling was Leonard Stayton of Inez, KY. The attorneys for the Department of Labor’s Solicitor’s Office (which sided with Mr. Epling) were Sean Bajkowski, Gary Stearman, and Sarah Hurley. The attorneys for Hobet Mining, LLC were Bill Mattingly and Ashley Harman.

2 Responses to “Important Black Lung Decision: Fourth Circuit Affirms Miner’s Award in Hobet Mining, LLC v. Epling, Discredits Physician’s “Argue in the Alternative” Opinion”

Just like to say that my dad had Mr staton for a lawyer for many years. My daddy passed away in 2013 still waiting for black lung benefits. He was diagnosed with stage 4 pneumocosis many years before he passed. He always said if I don’t get it then maybe your mommy will. Daddy worked in the mines for Wolf Creek Colliers 20 some years before becoming disabled. Yet I see and hear if men getting their benefits with less years and in much better shape. I could go on and on. My daddy was Okey Lee Mills a proud miner left without. Now where’s the judges

My husband worked thirty four years in and around the mines, he had been told years ago he had Black Lung, he went on working till they refused to let him go back, he worked after heart attacks, strokes. Surgery ,open heart, shoulders,colon . And many boughs of sickness. He retired in 2007 and filed for Black Lung, his heart rate was so low the Doctor would not give him the test and filed the report that he would not take it. 2013 he filed again and did it all and the report said he was “just below the state level.” So of course he didn’t have to them. Now he’s gone and I filed and going through the same thing. I am not giving up . He helped make millions for that company and they a keep the back pay I just want that little dinky check for him. Laws need changed . They just might start calling them races! LOL . Cop. Should be as honest as the workers. Thank you Darlene Keeton

Comments are closed.