Fourth Circuit Vacates Miner’s Award, Holds that ALJ Erred by Excluding CT Scan Readings, Weighing X-rays by Headcount, and Insufficiently Explaining Weight Given to Medical Opinions (Sea “B” Mining Co. v. Addison)

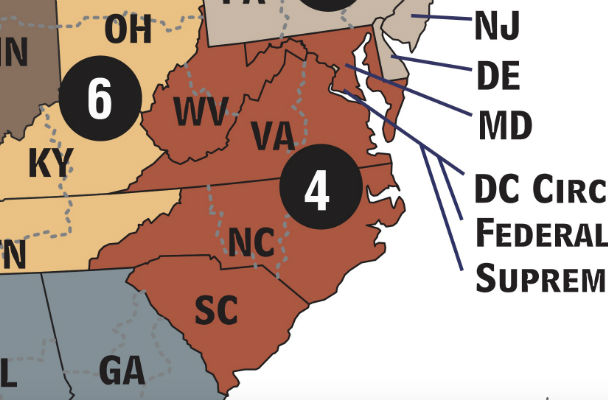

On Friday, July 29, 2016, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit issued a precedential “for publication” decision in Sea “B” Mining Co. v. Addison, 831 F.3d 244 (4th Cir. 2016) (slip op. available here) that vacated a disabled miner’s award of benefits. The Fourth Circuit held that the ALJ committed reversible error by excluding CT scan readings and in failing to provide sufficient explanations for how he weighed the x-ray readings and medical opinions. Addison is a rare Court of Appeals decision that disagrees with the Benefits Review Board on whether substantial evidence supports an award of benefits. Although parts of the court’s opinion are written broadly, when the court’s holding are understood within the context of the case, their effect should be limited—but notable—in federal black lung practice.

Facts

Jerry K. Addison worked as an underground coal miner for 11.7 years. He was also a smoker, with a pack-a-day habit from 1956 to sometime between 2001 and 2012. The parties agreed that towards the end of his life, Mr. Addison suffered from disabling breathing problems. However, the parties disagreed about whether Mr. Addison suffered from pneumoconiosis and whether it was a substantial cause of his respiratory disability.

Mr. Addison supported his claim by relying on the Department of Labor’s complete pulmonary examination from 2011 performed by Dr. J. Randolph Forehand, a physician who regularly performs black lung examinations and is a B-reader, but whose specialty by training is as a pediatrician and allergist. Dr. Forehand read Mr. Addison’s x-ray as positive for coal workers’ pneumoconiosis and said that Mr. Addison’s exercise arterial blood gas (ABG) results showed a disabling impairment that was caused by coal-mine dust.

Sea “B” Mining Co. contested Mr. Addison’s claim by submitting opinions by Dr. Gregory J. Fino and Dr. James R. Castle who both said that Mr. Addison’s problems were caused by idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, not pneumoconiosis. Dr. Fino said that looking at Mr. Addison’s radiological evidence longitudinally, his problems worsened too rapidly to be related to coal-mine dust and the radiological evidence showed fibrosis that was diffuse and not nodular. Dr. Fino also emphasized the restrictive nature of Mr. Addison’s pulmonary impairment.

The x-ray evidence was mixed, consisting of differing opinions of three x-rays from January 2009, February 2011, and May 2011. They were each read as positive by Mr. Addison’s experts and negative by Sea “B” Mining’s experts. Sea “B” Mining also offered three CT scan readings, all negative for pneumoconiosis.

ALJ Decision

The ALJ (Judge Henley) awarded benefits to Mr. Addison. (ALJ Decision here).

Regarding the presence of pneumoconiosis, the ALJ weighed the x-ray, CT scan, and medical opinion evidence separately.

The ALJ weighed the x-rays by comparing the physician’s readings of each x-ray. Thus, because Mr. Addison’s and Sea “B” Mining’s experts offset each other, the first two x-rays were found to be in equipoise while the third x-ray had Dr. Forehand’s reading as a tiebreaker, resulting in a finding that the x-ray evidence was, on balance, positive for pneumoconiosis.

The ALJ decided that Sea “B” Mining could only submit one CT scan reading as admissible “other medical evidence” under 20 C.F.R. § 718.107. This CT reading weighed against a finding of pneumoconiosis.

Regarding the medical opinions, the ALJ gave Dr. Forehand’s opinion more weight because the ALJ found it consistent with the Department of Labor’s position in the preamble (to the 2001 amendments to the regulations) that coal-mine dust and smoking have an additive effect in causing obstructive impairments. The ALJ discredited Dr. Fino’s and Dr. Castle’s opinions for overemphasizing the significance of the restrictive nature of Mr. Addison’s impairment and for being based on generalities.

The ALJ concluded that Mr. Addison proved that he had both clinical and legal pneumoconiosis and that it was a cause of his respiratory disability. Accordingly, the ALJ awarded benefits to Mr. Addison.

Benefits Review Board Decision

The Benefits Review Board affirmed the ALJ’s decision in a divided opinion (BRB decision here). The Board said that the ALJ erred by excluding two of the three CT scans but that this error was harmless because Sea “B” Mining did not specifically explaining how consideration of the other two CT scans would have made a difference. The Board also affirmed the ALJ’s decision of how to weigh the evidence.

Fourth Circuit Opinion

In a published opinion by Judge Agee (joined by Judges Niemeyer and Duncan) the Fourth Circuit vacated and remanded the Board’s decision affirming the ALJ’s award.

The Fourth Circuit issued holdings on three issues:

- An ALJ Must Consider One Reading of Each CT Scan, and the ALJ’s Error in Mr. Addison’s Claim Was Not Harmless. The Fourth Circuit agreed with the Board that the ALJ erred by excluding two of the three CT readings that Sea “B” Mining submitted. “Sea-B was entitled to submit, and the ALJ was required to consider, one reading of each CT scan under 20 C.F.R. § 718.107.” (slip op. at 16). The court differed with the Board though and held that the ALJ’s error was not harmless because, on the specific facts of Mr. Addison’s case, failing to consider all of the CT scan evidence affected the ALJ’s analysis of the evidence. For example, Dr. Fino’s rationale about the significance of the progression of the radiological evidence depended on all three of the CT readings and the ALJ did not address this argument. “Further, the CT scans would have contradicted the ALJ’s findings as to the x-ray evidence.” (slip op. at 19). However, the court rejected Sea “B” Mining’s argument that exclusion of admissible evidence is per se reversible error, instead an affected party has the burden to show prejudice that was likely to affect outcome or impact the public perception of the proceeding.

- An ALJ Cannot Implicitly Resolve Differing X-ray Readings By “Headcount.” The Fourth Circuit disagreed with the Board regarding whether the ALJ gave sufficient reasons to explain how he weighed the x-ray evidence. The court stated that based on its prior precedent, a decision cannot be based on “numerical superiority of the same items of evidence” and that a “numerical headcount” is “‘hollow’ and not consistent with an ALJ’s duties in making a reasoned decision.” (slip op. at 23–24). The court remanded so that the ALJ could “provide an explanation for his decision concerning the May 20 x-ray by explaining how he weighed the evidence ‘in light of the readers’ qualifications’ and whether his conclusion was based on a numerical headcount of experts.” (slip op. at 25).

- The ALJ’s Reasons for Crediting Dr. Forehand’s Opinion Were Not Sufficient. In a heavily factbound holding, the Fourth Circuit also disagreed with the Board regarding whether the ALJ sufficiently explained why he gave weight to Dr. Forehand’s medical opinion over the other physicians’.

The ALJ credited Dr. Forehand’s diagnosis based on its purported consistency with the following passage from the preamble to the amended regulations: “Coal dust exposure is additive with smoking in causing clinically significant airways obstruction and chronic bronchitis.” It is well settled that a factfinder may consult the Act’s preamble in assessing medical opinion evidence. Nevertheless, the ALJ erred in relying on this passage here because it has no bearing on Dr. Forehand’s pneumoconiosis opinion.

Although Dr. Forehand diagnosed Addison with an obstructive impairment, he attributed that impairment solely to cigarette smoking and found it non-disabling. Dr. Forehand’s diagnosis of legal pneumoconiosis, instead, was based on an arterial blood gas study showing weakened gas exchange and the May 2011 x-ray, which he concluded would have been different had Addison never been exposed to coal dust. However, Dr. Forehand never says why he reached that conclusion, particularly since he never found coal dust expoure related to Addison’s obstructive impairment. Quite the opposite, Dr. Forehand’s opinion contradicts the preamble text, as he found the obstructive respiratory impairment was attributed entirely to smoking without any aggravation from coal dust exposure.

(slip op. at 26–27) (internal citations omitted). The court also noted the difference in Dr. Forehand’s training from Dr. Fino’s and Castle’s (i.e., Dr. Forehand is board certified in pediatrics and allergies while Drs. Fino and Castle are board certified in internal medicine and pulmonary disease) and said, “The ALJ should have given some reasoned explanation as to why Dr. Fino’s and Dr. Castle’s superior qualifications did not carry any weight in his evaluation.”

The Fourth Circuit thus remanded with instructions to return Mr. Addison’s case to the ALJ for reconsideration.

Analysis

What stands out the most about the Fourth Circuit’s decision in Addison is the court’s factual focus and detailed attention to the ALJ’s reasoning. While most black lung cases at the Court of Appeals level that turn on the weighing of medical evidence take a “light touch” review and focus on the question of whether substantial evidence exists, Addison focused much more on what the ALJ wrote, not on what evidence existed.

The holding regarding the CT scans is sensible on the facts of Mr. Addison’s case, but worrisome when taken out of context. The court’s statement that “Sea-B was entitled to submit, and the ALJ was required to consider, one reading of each CT scan under 20 C.F.R. § 718.107” fails to account for the fact that even one reading of each radiological study can be cumulative and thus unnecessary to admit. In Mr. Addison’s case, because the operator’s defense was based in part on the longitudinal nature of the CT scans, then one reading of each CT scan made sense. However, in most cases the CT scans are not presented as a part of a discussion regarding disease progression and instead focus on the binary question of whether pneumoconiosis is present on a given CT scan. In the more typical pattern, allowing for one reading of each CT scan is in tension with the limit on x-ray readings (for which each party can only affirmatively submit two readings regardless of the number of x-rays taken, see 20 C.F.R. § 725.414). And because one of the reasons of the Department of Labor’s evidentiary limitations on x-rays was the fact that many miners cannot afford to develop expert readings of each x-ray, CT scans present even more of an issue because an expert CT reading tends to cost two to four times as much as an x-ray reading—exacerbating the disadvantage that miners or widows who lack much money face in the black lung benefits system. Addison’s statement regarding the required admissibility and consideration of CT readings then is best understood in the context of a case where a reading of each CT scan presented a longitudinal picture that was otherwise lacking.

Regarding the x-ray evidence, the court’s criticism of “headcounting” is not new, but the court should have clarified that counting the number of readers who provided opinions can be valid after considering qualitative factors such as credentials and general credibility. The court criticized a numerical approach to weighing x-ray evidence but then said in its remand instructions that the ALJ should explain “whether his conclusion was based on a numerical headcount of experts.” If headcounting is error, then why did the court include this in its remand instructions? The court should not be understood as setting the ALJ up for reversal by inviting error. Instead, the court’s remand instruction can be understood as being consistent with the Sixth Circuit’s decision in Sunny Ridge Mining Co. v. Keathley, 773 F.3d 734 (6th Cir. 2014), which held that a quantitative approach can properly be used as long as it is not the sole basis for the ALJ’s weighing of the evidence. In other words, counting heads can be proper, but an ALJ should be explicit and not base a decision solely on numerical superiority.

Regarding the weight to be given to Dr. Forehand’s opinion, because it is so case-specific it is hard to generalize from it, but the main take away is related to Dr. Forehand’s credentials. The court equated board certifications with “superior qualifications.” Board certifications are of course relevant, but so are other factors such as professional experience and the quality of the physician’s explanation. I do not know anything beyond the public decisions about Dr. Forehand’s opinions in Mr. Addison’s claim. But from what I know about Dr. Forehand more generally, his knowledge, experience, and interest in black lung matters is exceptional and his reasoning tends to be clear and thorough. Just as Dr. Donald Rasmussen became a singularly respected black lung examiner even though he was not a pulmonologist by training, see Martin v. Ligon Preparation Co., 400 F.3d 302, 307 (6th Cir. 2005), Dr. Forehand could similarly be given weight based on his experience and reasoning. The Fourth Circuit’s opinion in Addison suggests that parties using Dr. Forehand would be wise to build a record around his qualifications to show that board certification is not the only factor.

—

Mr. Addison was represented by Jerry Murphree of Stone Mountain Health Services before the ALJ, no one before the BRB, and Joe Wolfe, Esq. & Victoria Susannah Herman, Esq. of Wolfe, Williams & Reynolds before the Fourth Circuit.

Sea “B” Mining Co. was represented by Timothy Ward Gresham of PennStuart.

The Department of Labor’s Solicitor’s Office does not appear to have participated in the case.