Fourth Circuit Rejects Coal Company’s Doctor’s FEV1/FVC Theory, Affirms Miner’s Award of Benefits (Westmoreland Coal Co. v. Stallard)

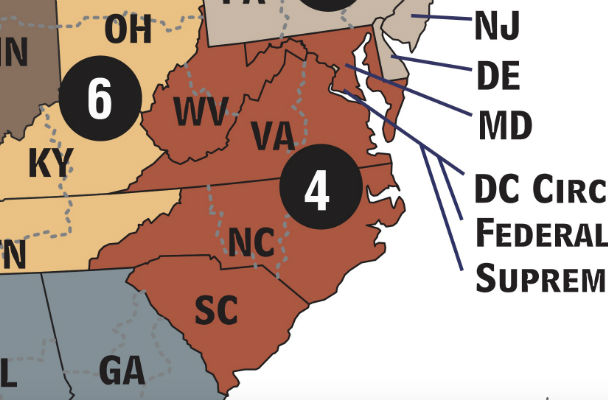

Yesterday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit issued a precedential “published” opinion affirming a coal miner’s award of federal black lung benefits.

In Westmoreland Coal Co. v. Stallard, 876 F.3d 663 (4th Cir. Nov. 29, 2017) (slip opinion available here), the Court held on four issues: timeliness of Mr. Stallard’s claim, the ALJ’s weighing of the evidence regarding Mr. Stallard’s smoking history, the ALJ’s rejection of a broad medical theory offered by Westmoreland Coal’s expert, and the ALJ’s weighing of the evidence under the “rule out” standard.

The most significant holding is the third, having to do with a particular medical measure of lung function called the “FEV1/FVC” ratio. In recent years, this ratio has been widely used by doctors hired by coal companies to argue that the effects of coal-mine dust and cigarette smoke can be distinguished in causing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In Stallard, the Court held that an ALJ properly rejected this theory for being contrary to the black lung benefits regulations and the Department of Labor’s preamble explaining the medical basis for its 2001 amendments to the regulations.

The Court’s decision provides binding authority in claims arising from states like West Virginia and Virginia that “ALJs are permitted to give less weight to medical opinions that draw on medical studies purporting to distinguish between smoking-induced COPD and black lung disease.”

This is a major win for coal miners and their families.

(Disclosure: While I do not represent Mr. Stallard, I represent other claimants in cases before the Fourth Circuit raising some of the same issues.)

Facts

Herksel Stallard is a Virginia coal miner who worked as a miner for more than thirty years, much of it for Westmoreland Coal. He was also a smoker, with the reports of his smoking history varying from a minimal history of just a cigarette or two per day all the way up to an extensive history of forty pack years. Mr. Stallard was diagnosed with black lung that was “not real severe” in 1990. Then in 1993, Mr. Stallard’s career as a miner ended after he suffered from carbon monoxide poisoning while on the job. When being treated for this, two doctors advised him not to return to work due to his breathing. Mr. Stallard also stopped smoking at this time.

In 2011, Mr. Stallard filed a claim for federal black lung benefits. In this claim, four doctors provided reports about Mr. Stallard’s lungs. The two doctors hired by Westmoreland Coal (Dr. David M. Rosenberg and Dr. George L. Zaldivar) said that Mr. Stallard’s breathing problems were not related to coal-mine dust.

In 2014, a Department of Labor ALJ (Judge Henley) awarded Mr. Stallard benefits (ALJ decision here). In this decision, the ALJ first rejected Westmoreland Coal’s argument that Mr. Stallard filed his claim too late. Weighing the varying smoking histories, the ALJ credited Mr. Stallard’s testimony that he was a light smoker with only a 2 to 4 pack year smoking history.

In weighing the physician’s medical opinions, the ALJ rejected Dr. Rosenberg’s theory that he could use the FEV1/FVC ratio to distinguish the effects of coal-mine dust and cigarette smoke in causing Mr. Stallard’s COPD. The ALJ also weighed the medical opinions more generally and found that Westmoreland Coal’s experts opinions were contrary to the facts (e.g., they overstated Mr. Stallard’s smoking history) and the Department of Labor’s medical conclusions from its Preamble to its 2001 amendments to the black lung benefits regulations.

The Benefits Review Board affirmed the ALJ’s award in 2016 (Board decision here).

Fourth Circuit Decision

In a decision by Circuit Judge James A. Wynn, Jr. that was joined in full by Circuit Judge Barbara Milano Keenan and District Judge John A. Gibney, Jr., the Fourth Circuit affirmed Mr. Stallard’s award of benefits.

The Court issued four holdings:

- Mr. Stallard’s Claim Was Not Filed Too Late. The Black Lung Benefits Act requires that claims be filed within 3 years of “a medical determination of total disability due to pneumoconiosis.” 30 U.S.C. § 932(f). Westmoreland Coal argued that, taking these medical determinations together, because Mr. Stallard was told in 1990 that he had black lung and advised in 1993 that he should stop working, that his time limit expired far before he filed in claim in 2011. The Fourth Circuit rejected this argument because “No one doctor communicated to Stallard a diagnosis of both total disability and black lung disease.” The Court pointed out that the 1990 diagnosis of black lung said that it was “not severe” and “left open the possibility of Stallard returning to work.” And in 1993, the physicians merely advised Mr. Stallard not to return to work “and did not identify any underlying cause.” The Fourth Circuit thus concluded that given the “imprecise nature” of the medical determinations, “Stallard was never legally notified that he was totally disabled due to black lung disease.”

- The ALJ’s Finding Regarding Mr. Stallard’s Smoking History Is Supported by Substantial Evidence. Westmoreland Coal argued that when the ALJ found that Mr. Stallard only smoked a cigarette or two per day for 39 years (and thus had a 2 to 4 pack year history) the ALJ did not sufficiently account for evidence that Mr. Stallard smoked more. The Fourth Circuit rejected this factual dispute and said that “the totality of evidence on this front is largely inconsistent” and that the ALJ considered Westmoreland Coal’s argument but chose to credit Mr. Stallard’s testimony instead. The Fourth Circuit explained “although the ALJ here chose to accept the lower end of a relatively wide range of evidence, we have stressed that we must ‘be careful not to substitute our judgment for that of the ALJ.'” (quoting Harman Mining Co. v. Director, OWCP [Looney], 678 F.3d 305, 310 (4th Cir. 2012)).

- The ALJ Properly Rejected Dr. Rosenberg’s FEV1/FVC Theory. Westmoreland Coal raised a technical, medical issue and argued that the ALJ erred in discounting Dr. Rosenberg’s use of Mr. Stallard’s FEV1/FVC ratio to explain why he did not think that coal-mine dust contributed to Mr. Stallard’s disabling COPD. The Fourth Circuit affirmed the ALJ’s rejection of this theory:“Dr. Rosenberg’s hypothesis regarding FEV1/FVC ratios runs directly contrary to the agency’s own conclusions in this regard. Specifically, the Labor Department’s regulatory Preamble cites various studies indicating that coal dust exposure does result in decreased FEV1/FVC ratios. See Regulations Implementing the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969, as Amended, 65 Fed. Reg. 79,920–01, 79,943 (Dec. 20, 2000) (explaining that COPD stemming from exposure to coal dust “may be detected from decrements in certain measures of lung function, especially FEV1 and the ratio of FEV1/FVC” (emphasis added)). The Preamble is consistent with the corresponding regulation permitting claimants to demonstrate entitlement to Black Lung Act benefits based on a reduced FEV1/FVC ratio. 20 C.F.R. § 718.204(b)(2)(i)(C). It is appropriate to give “little weight … to medical findings that conflict with the [Black Lung Act]’s implementing regulations.” Lewis Coal Co. v. Dir., Office of Workers’ Comp. Programs, 373 F.3d 570, 580 (4th Cir. 2004). And, under substantially similar circumstances, we have held that ALJs are permitted to give less weight to medical opinions that draw on medical studies purporting to distinguish between smoking-induced COPD and black lung disease. See [Westmoreland Coal Co. v. ]Cochran, 718 F.3d [319,] 323–24 [(4th Cir. 2013)].”

Slip Op. at 14–15. And while Dr. Rosenberg said that he relied both on medical studies from before and after the Preamble (published in 2000), the Fourth Circuit said that his interpretation was based on “selective quotations” of the older studies that were contrary to the agency’s interpretation and “the more recent studies do not address black lung disease at all.”The Fourth Circuit then pointed out that it had previously rejected the FEV1/FVC theory in unpublished decisions and the Sixth Circuit had rejected the theory in published and unpublished decisions. The court concluded: “In light of these authorities, as well as an ALJ’s general prerogative to discount medical opinions at odds with the conclusions adopted by the agency itself, we conclude that the ALJ did not err in rejecting Dr. Rosenberg’s opinion regarding the FEV1/FVC ratio’s ability to show particularized causation.”

- The ALJ Properly Applied the “Rule Out” Standard In Finding That Westmoreland Coal Did Not Rebut the Fifteen-Year Presumption. Lastly, the Fourth Circuit affirmed the ALJ’s rebuttal analysis under which he considered whether Westmoreland Coal could “rule out” a relationship between Mr. Stallard’s pneumoconiosis and his respiratory disability. Westmoreland Coal argued that the ALJ created an “impossible standard” by applying the Preamble’s recognition that coal-mine dust has an additive risk with cigarette smoke in causing pulmonary impairments to the strict “no part” (a/k/a “rule out”) rebuttal standard regarding the fifteen-year presumption. The Fourth Circuit said that “this argument contradicts both the regulations and our precedent” and explained that the ALJ properly applied the Preamble when weighing the contrasting physicians’ opinions. “The decision below carefully laid out the components of each doctor’s diagnosis and underlying rationales. The decision then meaningfully engaged with the medical science, relevant caselaw, and applicable regulations.”

The Fourth Circuit thus affirmed Mr. Stallard’s award of benefits.

Analysis

Stallard is a significant decision in favor of black lung benefits claimants.

The most notable holding is the one regarding the FEV1/FVC ratio. The Fourth Circuit unequivocally rejected this theory. The court’s language on this subject was strong. It said that Dr. Rosenberg’s hypothesis is “directly contrary to the agency’s own conclusions” while the “Preamble is consistent with the corresponding regulation.” The Court then said an ALJ may give “little weight … to medical findings that conflict with the [Black Lung Act]’s implementing regulations” and “medical opinions that draw on medical studies purporting to distinguish between smoking-induced COPD and black lung disease.”

This strong language should discourage future reliance on FEV1/FVC ratio and other similar methods that purport to be able to differentiate between COPD caused by coal-mine dust and COPD caused by cigarette smoke.

Stallard is also the Fourth Circuit’s strongest holding in support of ALJs’ discretion to use the Preamble in assessing the credibility of medical experts in black lung benefits claims. The court held that because the Preamble was the “product of notice-and-comment rulemaking, this Court must accord these conclusions substantial deference.” The Fourth Circuit then applied the Preamble both in rejecting the FEV1/FVC theory and in affirming the ALJ’s weighing of the medical opinions.

The statue-of-limitations holding does not break new ground but provides a clear example that a miner’s period to file a claim does not start running until a physician connects the miner’s black lung with his respiratory disability and communicates this to the miner. A miner does not have a legal duty to synthesize medical determinations and decide himself whether one doctor’s diagnosis of black lung is the cause of another doctor’s opinion that he is has a respiratory disability.

The rest of the decision is mostly limited to the specific facts of Mr. Stallard’s case (for example, his smoking history) but Stallard reiterates the limited role of federal, Article III judges in reviewing factual findings by ALJs and the strict nature of the rebuttal standard under the fifteen-year presumption.

With only a month left in the year, Stallard is the Fourth Circuit’s only precedential decision in a black lung benefits case in 2017. (The last published decision regarding the medical merits of a claim was last year’s decision vacating an award of benefits in Sea “B” Mining Co. v. Addison (see previous post here).)

Stallard is the latest in a string of black lung benefits cases before the Fourth Circuit involving the fifteen-year presumption (which the Affordable Care Act revived in 2010). At this point the court has rejected all of the broad legal and medical theories that coal companies have offered to meet their rebuttal burden.

Stallard is a major win for disabled coal miners who spent at least fifteen year working in underground and dusty surface mines and for the continuing power of the Department of Labor’s thorough analysis of the medical literature regarding the effects of coal-mine dust on miners’ lungs in its Preamble to the 2001 amendments to the regulations.

—

Herskel Stallard was represented by Joe Wolfe, Esq. of Wolfe, Williams & Reynolds of Norton, Virginia.

Westmoreland Coal Co. was represented by Fazal Afaque Shere, Esq. & Paul E. Frampton, Esq. of Bowles Rice LLP in Charleston, West Virginia.

The Director, OWCP was represented by Barry H. Joyner, Esq. and Rebecca J. Fiebig, Esq. of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Solicitor’s Office.

One Response to “Fourth Circuit Rejects Coal Company’s Doctor’s FEV1/FVC Theory, Affirms Miner’s Award of Benefits (Westmoreland Coal Co. v. Stallard)”

Good Job Mr Wolfe

Al South

Comments are closed.